Je n’ai jamais lu la nouvelle d’Ursula Le Guin The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas (Ceux qui quittent Omelas) mais j’aime bien ce que Graeber et Wengrow en citent dans The Dawn of Everything: “Omelas…une ville qui…se passait de rois, de guerres, d’esclaves ou de police secrète. Nous avons tendance, note Le Guin, à faire une croix sur de telles communautés, en les traitant de ‘simples’, mais en fait, ces citoyens d’Omelas n’étaient pas des “gens simples”, des bergers-bergères suaves, de nobles sauvages, de pâles utopistes. Ils n’étaient pas moins complexes que nous.’ L’ennui, c’est simplement que ‘nous avons l’habitude, encouragés en ça par les pédants et les gens sophistiqués, à considérer le bonheur comme quelque chose d’assez stupide.”

Très juste. “Les peuples heureux n’ont pas d’histoire”, et cetera. Traduction: le malheur (des autres), y a que ça d’intéressant. (Ou pensez à l’homme riche dans la fable d’Italo Svevo qui se retrouve accidentellement au paradis et qui réclame d’être re-dirigé vers l’enfer parce qu’il ne peut pas supporter la vue de tous ces bienheureux.)

Et pourtant, quand le malheur frappe pour vrai – guerres, révoltes, séismes… de quoi sont faits les souvenirs de tous un chacun ? D’un après-midi ensoleillé avec des amis, d’un repas en plein air après une cueillette de cerises, d’un moment de bonheur à barboter dans une eau claire…

Pour une raison quelconque, Sturm und Drang ont une bien meilleure cote.

Cela dit, j’ai presque terminé la lecture de The Dawn of Everything, avec le sentiment d’être un peu surchargée de tant d’informations méconnues concernant un (des) passé(s) qu’on s’acharne à nous présenter comme une marche ordonnée depuis le crétinisme de nos ancêtres du néolithique jusqu’à l’intelligence exceptionnelle des lanceurs de satellites et fabricants de brosse à dents électroniques qui nous enchantent présentement.

Il est bon de lire autre chose, même s’il me faudra un bon moment pour décanter autant d’informations fascinantes glanées sur tous les continents.

Et j’écris. Avec difficulté, ces jours-ci, et sans me faire trop d’illusion sur la réception que mes mots auraient chez les pédants et les sophistiqués qui défilaient dans mes rêves, la nuit dernière.

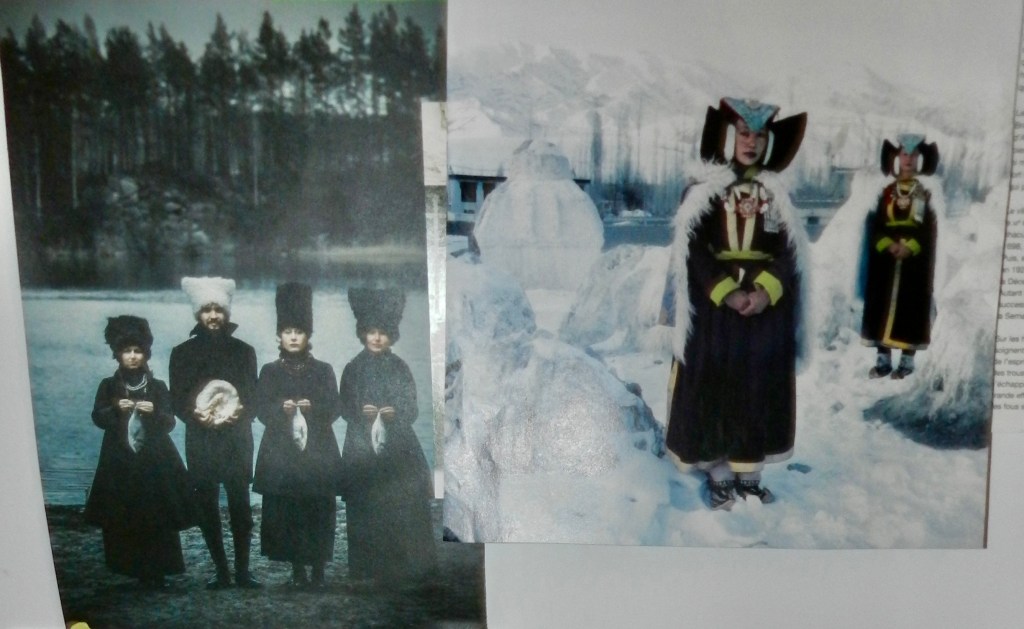

(L’illustration n’a rien de spécial à apporter au texte. Elle fait partie des images qui font la rotation sur mon frigo, et elle est plus intéressante à regarder que la vue depuis ma fenêtre ce matin.)

*

I’ve never read Ursula Le Guin’s short story Those Who Walk Away from Omelas but I like what Graeber and Wengrow have to say about it in The Dawn of Everything: “Omelas…a city that…made do without kings, wars, slaves or secret police. We have a tendency, Le Guin notes, to write off such a community as ‘simple’, but in fact these citizens of Omelas were ‘not simple folk, not dulcet shepherds, noble savages, bland utopians. They were not less complex than us.’ The trouble is just that ‘we have a habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid.”

Quite so. “Happy people have no history”, etc. Translation: unhappiness (of others), that’s the only thing of interest. (Or think of the rich man in Italo Svevo’s fable, finding his way accidentally to heaven, and demanding to be sent down to hell because he can’t stand the sight of all these blissful people…)

And yet, when misfortune strikes for real – wars, rebellions, earthquakes …what are everyone’s best memories made of? Of a sunny afternoon with good friends, of an outdoor meal after picking cherries, of a blissful moment wading in clear water…

For some reason, Sturm und Drang rate much, much higher.

That said, I’m almost done reading The Dawn of Everything, with a feeling of being somewhat loaded down with so much unknown information about the past(s) we are constantly told consists of some well-ordered march forward from the idiocy of our Neolithic ancestors to the supreme intelligence of our times’ launchers of space ships and manufacturers of electronic tooth brushes delighting our days.

It’s good to read something else, even if I’ll need a good while to let settle all the fascinating information gleaned from everywhere on earth.

And I write. With difficulty, these days, and without too many illusions about how my words would be greeted by the pedants and the sophisticates who streamed through my dreams last night.

(The illustration has nothing special to say about any of this. It’s part of the changing vista on my fridge and more interesting than the view out the window this morning.)