Les jours d’après –

Je ne crois pas que le nom et l’oeuvre d’Evgueny Schwartz soit très connus. Ce qu’il importe de savoir ici, c’est qu’il a écrit en Union soviétique durant les pires années du totalitarisme stalinien et que ces contes et pièces de théâtre, supposément pour enfants, se voyaient régulièrement censurées et interdites car, sous le roi nu ou le dragon, il ne fallait pas chercher très longtemps pour sentir les pics de la critique contre le système.

Je pense à Schwartz, et plus précisément au Dragon, son conte en trois actes, en raison du phénomène constamment récurrent qui se déroule encore une fois, suite aux réactions à l’assassinat en direct d’un homme à la peau noire aux Etats Unis. La question que je me pose est de savoir ce qu’il s’ensuivra, une fois que seront retombées l’indignation et la rage initiales.

Dans Le Dragon, un homme du nom de Lancelot ( un noble descendant de l’original, et tueur de dragon comme son ancêtre) arrive dans un village et pénètre dans une maison dont toutes les portes et fenêtres sont ouvertes. Il n’y a personne sauf pour un chat auquel il demande si ses maîtres seront bientôt de retour. Le chat ne dit rien sauf :

Le chat – Je me tais.

Lancelot – Et pourquoi, si je puis me permettre ?

Le chat – Quand on est tranquille bien au chaud, il est plus sage de somnoler et de ne pas trop en dire, mon très cher.

Lancelot – Mais quand même, tes maîtres, où sont-ils ? (…) Ah, c’est donc ça. Un malheur les menace ? Et le lequel ? Tu te tais ?

Le chat – Je me tais.

Lancelot – Pourquoi ?

Le chat – Quand on est tranquille bien au chaud, il est plus sage de somnoler et de ne pas trop en dire que de fouiller dans un avenir déplaisant. Miaou !

Lancelot se chargera de tuer le dragon à trois têtes mais le conte ne s’arrête pas là. Parce que, comme lui dit la troisième tête du dragon : “Ce qui me console, c’est que je te laisse des âmes brûlées, des âmes trouées, des âmes mortes…”

Ce qui fait que, à la fin du conte, le véritable travail consistera à se débarrasser du dragon intérieur dans chacun. (Ou comme disait Pogo, mon personnage préféré d’une bande dessinée de mon enfance : “Nous avons trouvé l’ennemi, et l’ennemi, c’est nous.”)

Nous sommes plus ou moins habitués (au point d’en devenir stupéfiés) par la violence qu’on qualifie d’inadmissible sans que ça y change grand chose, violence infligée aux civils dans les zones de guerre, et beaucoup moins sensibles à la violence insidieuse et sytémique qui se déroule quotidiennement autour de nous. Et d’après les commentaires que je lis, beaucoup d’américains en sont encore à se demander si le problème ne pourra pas se résoudre par la mise au rancart de quelques statues… Raison pour laquelle j’ai cité l’échange entre Lancelot et le chat qui aime son confort par-dessus tout…et qui aura besoin d’une rencontre avec un âne et une bonne dose de l’entêtement de ce dernier pour passer à autre chose…

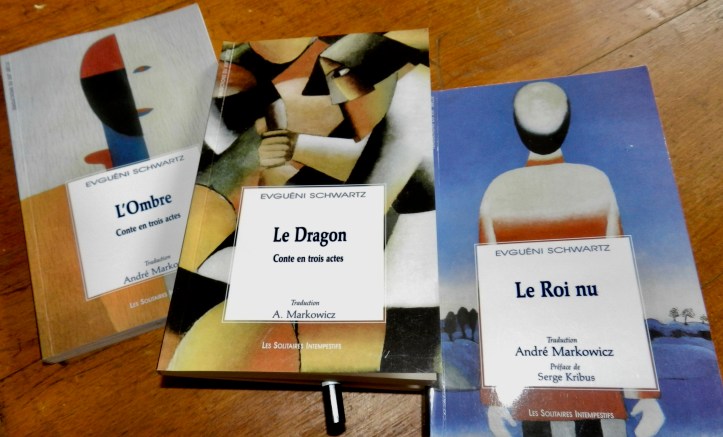

Illustration :

Evgueny Schwartz, L’Ombre, traduit par André Markowicz, éditions Les solitaires intempestifs, 2011

Evgueny Schwartz, Le Dragon, traduction André Markowicz, éditions les solitaires intempestifs, 2011

Evgueny Schwartz, Le Roi nu, traduction André Markowicz, préface de Serge Kribus, Les solitaires intempestifs, 2003

*

The Days After –

I don’t think the name and work of Evgeny Schwartz is very well known. What matters here is the fact he wrote in the Soviet Union during the worst years of Stalinist totalitarianism and that his tales and plays, supposedly for children, were regularly censored and prohibited because, under the naked king or the dragon, you didn’t have to search too long in order to feel the stings of criticism against the system.

I’m reminded of Schwartz, and more specifically of The Dragon, his tale in three acts, because of the ever-recurring phenomenon, currently playing out, yet again, this time over reactions to the on-line killing of a black man in the United States. And the questions I ask myself about what comes next, once the initial outrage and indignation simmer down.

In The Dragon, a man named Lancelot (noble descendant of the original, and dragon-slayer like his ancestor) arrives in a village and enters an empty house, where all doors and windows are open. No one is there except for a cat to whom he asks if his masters will be back soon. No answer from the cat except to say:

The cat – I am silent.

Lancelot – And why, if I may ask?

The cat – When you are warm and quiet, it is wiser to take a snooze and not say too much, my dear.

Lancelot – But still, where are your masters? (…)So that’s it. They are threatened by misfortune. By what? You keep silent?

The cat – I keep silent.

Lancelot – Why?

The cat – When you are warm and quiet, it is wiser to take a snooze and not say too much, instead of digging into unpleasant things to come. Miaow!

The slaying of a dragon by Lancelot will ensue but the tale doesn’t end there. Because as the dragon’s third head tells him: “My consolation is knowing that I leave you with burnt-out souls, souls filled with holes, dead souls…”

So, at tale’s end, the real job becomes one of dealing with the dragon within. (Or as my favorite cartoon figure when I was a child, Pogo, once said: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” )

We are more or less accustomed (to the point of stupor, in many cases) with the violence we call inadmissible without this making any difference, violence inflicted on civilians in war zones across the world, and much less attuned to the insidious systemic kind all around us. And seeing some of the comments I’ve been reading, many Americans are still under the impression that the problem might be solved by removing an offending piece of statuary or two. Which is why I quoted the exchange between Lancelot and the cat – who loves his comfort most of all…and will need a meeting with a mule and a heavy dose of mule-headedness of his own to move on.